In today’s complex world, how is it possible to truly live as a yogi? Traditional yoga theory offers fresh, insightful solutions to today’s practical lifestyle concerns, ranging from environmentalism to personal health and wellness. Tuning into classic yoga philosophy and teachings can bring to light our greatest strengths while showing us how to maintain a healthy body and clear mind while attaining inner happiness.

Drawing from his personal experiences of yoga and insight into ancient Sanskrit texts, Dr. Shankaranarayana Jois connects yogic philosophy to how we approach food, work, education, relationships, and other conscious lifestyle choices to support our deepest longings for happiness, peace, and balance.

Practical and insightful,The Sacred Tradition of Yoga begins with a clear and deep inquiry into the human condition, reminding us of true purpose of Yoga. The second half of the book focuses on the yamas and niyamas, the personal disciplines and social ethics of yoga. Throughout, Dr. Jois’ teachings honor ancient traditions and underscore the benefits we can gain from adopting a yogic way of life in the modern world.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part One: The Foundation of Yoga

1. The Purpose of Human Life

2. The Bliss of Samādhi

3. The Path to Realization

4. Mind and Body

5. The Human Predicament

6. Many Paths, One Goal

Part Two: Ashtanga Yoga – Yamas and Niyamas

7. The Yamas

Ahimsā · Satya · Asteya · Brahmacarya · Aparigraha

Dayā · Ārjava · Kṣamā · Dhṛti · Mitāhāra

8. The Niyamas

Śauca · Santoṣa · Tapas · Svādhyāya · Īśvara Praṇidhāna

Āstikya · Dāna · Hrīhi · Mati · Japa · Vrata · Siddhānta Śravaṇa

Part Three: The Yoga Journey

9. The Role of the Teacher

10. The Mango Orchard

11. Conclusion

Appendix 1: An Overview of the Traditional Branches of Yoga

Appendix 2: Sanskrit Pronunciation Guide

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

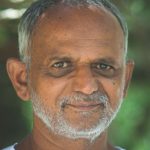

DR. SHANKARANARAYANA JOIS, PH.D. worked for decades both as a professor of Literature in Mysore College of Sanskrit and as a Vedic astrologer; however it is his own personal experiences of yogic states of consciousness that inform his teachings. Dr. Jois travels to deliver seminars and workshops to sincere practitioners across the world.

PREVIEW OF CHAPTER 1

***

bhumi: earth, foundation; bhumika: a small piece of earth; yogabhumika: the small

piece of earth which has brought about yoga, known as “Bharata,” or India.

***

Chapter 1

by K. L. Shankaranarayana Jois

THE PURPOSE OF HUMAN LIFE

I was born in a small village in the south Indian state of Karnataka by the name of Konandoor. At that time, this village had no electricity and no motor vehicles. At the early age of three, I was taken from this village to the home of my maternal grandmother in Shimoga. My grandmother was a very spiritual person and spent many hours each day chanting prayers. She was a devoted woman with firm principles, and often her practice included fasting. Two of my uncles lived there as well, completing their studies. Everyone in the house, me included, woke each day at 4:30 a.m.

Each year when the sun entered Sagittarius, my grandmother would begin a month-long practice of taking an early morning bath in the Tunga River, which flowed behind her house. It is the tradition in India to teach verses to children at a very early age—beginning with a salutation to the Eternal Teacher. On the way down to the river, she would teach me one line of a chant about the Eternal Teacher. It began, “Guru Brahma, Gurur Viṣṇuḥu, Guru Devo Maheśvaraḥa.” As she chanted, I would practice my lines over and over again, looking here and there, shaking from the cold water. My grandmother would stop to listen and remind me to keep my body still, hold my spine straight, and focus on my chanting. This was how reverence for the spiritual world was introduced to my life.

Long ago in India, most people were living an ideal way of life. It did not matter whether someone was a priest, a shopkeeper, a mayor of the village, or a laborer. Each lived life in a way that led naturally to certain yogic experiences. The entire society was set up so that, based on the constitution of the individual, all members would experience yoga. This included the practice of sitting quietly each day at sunrise and sunset in order to calm the mind. This was so integrated into daily life that it was not even considered to be “practice.” Rather, it was as natural as eating or sleeping.

Even fifty to one hundred years ago, people’s lifestyles were far more conducive to yogic principles than they are today. In many villages there was still no electricity, and a peaceful, and quiet, lifestyle was the only option. At nighttime, the only sources of light were lanterns, candles, and fire, so people would naturally go to sleep at the optimal time. The cultural support for quieting the mind, and achieving yogic experiences, was integrated into the very fabric of life.

OUR CHALLENGE TODAY

Today, all around the globe, we have fallen into hectic, fast-paced lifestyles. Many of the exotic foods available to us keep our bodies and minds overstimulated and out of balance. Television, radio, movies, and the Internet provide us with entertainment that does not have the goal of quieting the mind; on the contrary, these entertainments are often designed to stimulate the mind. Often, this stimulation disturbs us in ways we fail to notice. As a result, we have lost something dear. Most do not even know what is missing. We are oblivious to the pervasive deterioration of our fundamental human condition.

Unlike the people of the small town where I lived with my grandmother, people now live very busy lives. They rarely, if ever, provide time to experience conditions related to the yogic journey. There are few yogis to inspire us to live differently and few examples of people living an ideal yogic way of life. We simply end up following society’s trends and unconsciously pass them along to our children.

People today have lost many of the original capacities that yogis once saw present in all human beings. Like people addicted to drugs or alcohol, we have undergone a structural change in mind and body. This loss of our original condition, and its negative effects on the mind, body, and soul, is a tragedy. Because of these radical changes, even those who strive to do yogic practices may find it difficult and challenging at times. People despair that such clarity and focus are not possible in our world today. But the truth is that they are possible. Moreover, they are our birthright. And, to a large extent, that is the central theme of this book.

We have a great deal to learn about the actual impact of how we live our daily lives. The path of Aṣṭāṅga Yoga offers the practices and disciplines necessary to lead a life that is truly supportive of the highest form of human happiness. I refer to this as an ideal way of life, or lifestyle. I am also referring to the traditional definition of Aṣṭāṅga Yoga, rather than what has been popularized over the past several decades in the West. When we understand the connection between how we live our lives and our potential to achieve meaningful yogic experiences, we may then choose to make the necessary adjustments that can move us in the direction of Realization and Liberation.

THE PARABLE OF THE NOBLE PRINCE

Once a noble and powerful king ruled over a peaceful kingdom inhabited by honorable and worthy subjects. He dwelt in a beautiful palace with his wife and infant son. His kingdom was endowed with peace, contentment, and much material and spiritual wealth. All who lived there enjoyed a serene existence and lived in happiness.

One ill-fated day, the kingdom came under attack from a strong, malicious enemy. The king assembled his army and gathered all available resources to defend the kingdom. Though the king and his army fought valiantly, they were outnumbered and outmaneuvered. Eventually, the enemy overpowered the king’s army, seriously wounded the king, and took possession of the palace and the entire kingdom.

To preserve all that was dear to them, the king’s subjects helped him escape with his queen and their small son. They believed that if the king survived, so might their kingdom; if the king was killed, the kingdom would surely be lost forever.

The royal family left the palace and hid in a forest. They had no provisions, nor any means of acquiring them, and soon faced starvation. The king made every sacrifice possible for his child, feeding him all the food he could find. But one day, weak and exhausted, the king and queen died, leaving the helpless child alone. Eventually, the child crawled even deeper into the forest.

Soon afterward, a group of hunters came by chance upon the crying baby. They failed to recognize the baby as the crown prince, but they felt compassion for the small child and took him back to their village. There they fed and cared for him as one of their own. Naturally, as the boy grew, he adopted the language and traditions of his new family and the other village children. Living in a village of hunters, he, too, excelled in the skills of hunting, archery, and tracking wild game.

One day, the boy and his village companions were out hunting. In their quest, they chased game through the valleys, over hills, and through dense forests. In their enthusiastic pursuit, they lost track of their prey and became disoriented, unable to find the way back to their village. While searching for some clue to their whereabouts, they discovered a small āśrama in the forest. Curious, they entered and met the sage who lived there. This sage happened to be a Realized yogi, or ṛṣi, who understood the ancient science of guiding others to Realization. He possessed uncommon powers, including yogic sight, and could visualize the unseen workings of the whole universe. He was a deeply compassionate man, and everyone loved and honored him because of the guidance he offered.

This ṛṣi was a charming man who enjoyed engaging with these vibrant young hunters. He invited them to sit down and offered them delicious milk, food, and holy water. As the boys were eating and talking, the sage listened to their adventures with delight; everyone laughed until tears came to their eyes. One boy in particular caught the ṛṣi’s interest. This boy was not like the other boys. Through his yogic sight, the ṛṣi recognized that this boy was not the child of a hunter but actually the son of a king.

After the boys finished eating, the ṛṣi quietly took this one boy aside and asked, “Are you from the same village as your companions?”

“Yes, sir,” the boy replied. “We are all from the same village.”

“And is your father from this same village?” the ṛṣi inquired.

“Yes,” replied the boy. “However, he died when I was still a baby.”

I was raised by my uncle, whom I now regard as my father. He loves me as if I were his own son.”

“And your uncle is also a hunter?” asked the ṛṣi.

“Yes, he is,” said the boy.

The ṛṣi thought for a moment and then said gently, “My heart is

moved to tell you something: You are not the son of a hunter, but the son of a king. Truly, you are a prince!”

This surprised the boy tremendously. “Sir, I am afraid that I don’t understand. Am I somehow different from the other boys?”

“Yes,” the ṛṣi answered, “there is indeed a difference.”

The boy was suddenly filled with questions: “What is a prince? What are the differences between a prince and other boys? Do princes also hunt? What else does a prince do?”

As they were speaking, the other boys prepared to leave and approached the two. The ṛṣi quickly whispered to the boy, “I need to speak to you more when you have some time. Will you come visit me again?”

“Yes, sir,” answered the boy. “I would like to come back.”

“For now,” the ṛṣi counseled him, “keep this information to yourself. Until you understand more, it would be better not to talk about this to the others in your village.” He then gave the boys directions back to their village and sent them on their way home.

Honoring the ṛṣi’s advice, the boy told no one about the surprising revelation. He pondered over what the holy ṛṣi had said, asking himself, “Am I not a hunter’s son? How is it that I am a prince?”

Soon after, the boy returned to the āśrama, and the ṛṣi continued to explain, “A prince is the son of a kingdom’s ruler. He possesses extraordinary mental and physical capacities, and a powerful and charismatic personality. He enjoys great wealth and shoulders great responsibility because the whole kingdom belongs to him. He has control over it but uses that control only for the benefit of his subjects. And though he lives in a palace, his acts are service minded, because he is always thinking of the people’s welfare and of his duty as the prince of the kingdom.”

The boy did not comprehend entirely, but the information had a powerful effect on his mind. As time passed, he began to feel deep love and dedication toward the ṛṣi. He returned often to the āśrama. In due course, the ṛṣi gave further explanation.

“Though you dress like the rest of the villagers, the structure of your body is different from that of theirs, as are your eyes and your smile. Your body is well proportioned and noble in stature. Your forehead is large and your chest broad. Your trunk is lean like a lion, your legs are like pillars, and your arms long and powerful. And though you speak the same language, your speech carries far more impact.” The ṛṣi concluded, “These are the features of a prince.”

When the boy returned to his village, he would observe small differences between the other villagers and himself. In time, he realized that these differences were quite significant. The ṛṣi continued answering his questions, explaining the duties of a prince, and imparting wisdom to him. “You are a very powerful person,” the ṛṣi counseled. “Learn how to live up to your full potential.”

The boy’s princely qualities gradually became more and more evident with each passing day. As he gained new understanding, so grew his confidence and his ability to lead and influence others in the village. In time, he raised an army and returned to his real father’s kingdom. There, he defeated his father’s enemies and ascended the throne as the rightful heir.

OUR TRUE NATURE

How does this story relate to yoga? It is an allegory for the science of yoga itself. In its essence, it speaks of something at the very core of our human existence. Yoga recognizes that in this worldly kingdom, all of humanity is royalty. The Saṃskṛta word rāja means “king”; it is derived from the root rajru, meaning “light.” Rāja indicates both king and the Great Light, the Eternal Truth that is the source of this universe. It is what resides at the center of each and every heart. We are incarnations of this Eternal Truth and, as such, rightful heirs to a divine kingdom. Previously, we inhabited this kingdom and lived in its splendor. But just as the prince became lost in the forest, we, too, have become lost in our worldly affairs. Just as the young prince was ignorant of his true identity, we too are ignorant of the true nature of the Self. This is because we have become overpowered by delusion and attachment to this external world, swept up in life.

Ignorance leads us to think that this life, along with its daily challenges and material rewards, is the only possible option available to us. Caught by our powerful attachments, we unknowingly have abandoned our rightful glory. Over the ages, through many births and deaths, the memory of this glorious kingdom has been buried; we have forgotten who we are and where our original kingdom resides. What is more, we have forgotten that there is even anything to remember.

OUR CAPACITY TO ENJOY SOMETHING GLORIOUS

Like the prince who lived as a hunter’s child, we have adopted the lifestyle of those around us. Through the many daily activities and distractions we engage in, we have lost our connection to the glorious kingdom that was once our birthright. We once embraced an ideal way of life but now have discarded and forgotten what it means to live in such a way. Since we are no longer able to recollect these original experiences, we have given up the ideal way of life that supports them.

Moreover, not only have we forgotten who we truly are, we have developed highly injurious misconceptions and habits that rob us of our original inherent powers. Like the prince in the story, we have lost our capacity for enjoying something glorious, a natural bliss that would continuously fill our hearts if we were living in our original state. Having returned to the palace, the prince once again experienced power, glory, and his divine qualities. If we return to a pure and sound human mind and body, we, too, will be able to experience the magnificence and divinity of our original Self.

But how do we regain the capacity to experience such things? How can we see who we truly are? As children of the Eternal Truth, it is our right to experience the Eternal Truth in our daily lives and to enjoy the unsurpassed pleasure it brings. But to achieve this we need to be reminded of who we are. How is this possible? Who and what can help us achieve this?

THE SCIENCE OF YOGA

Yoga is a systematic and scientific method for awakening the memory of our original state. A proper yoga teacher knows how to remind the student who he or she truly is and how to stimulate and bring forth the student’s forgotten capacities. As a first step, the teacher catches the heart of the student and kindles the flame of desire for spiritual happiness. Then the teacher tames the student’s mind, so the intellect becomes an able and willing partner in the journey toward Realization. A teacher who is able to do this is an authentic teacher. This kind of teaching is only possible when it is derived from the teacher’s direct experience. When it comes from his heart, it can carry divine messages directly to the heart of the student. Only a person with sight can lead the blind; only one who has achieved Self-Realization can guide others to Enlightenment. Such a Realized being is the guru, or the Eternal Teacher.

A Realized person should remind us that we are not meant for suffering. Is suffering natural and intrinsic to our experience? Does some Divine entity bestow unhappiness upon us, and are we powerless to refuse it? Certainly not. We have created our own misery; we also have the capacity to eliminate it. It is not necessary to be unhappy. We have the right and capacity to live in a wonderful world filled with experiences of bliss. What keeps us from doing so? It is only our ignorance about who we are and where we have come from.

Education under a Realized person will enlighten us about ourselves. Gradually, we will be able to recognize our present condition and learn about our great internal capacity. His teachings will purify us, and we will gain insight into our own souls. We will see that we are the Eternal Truth and that our lost kingdom is to be found not outside ourselves, but within. In this way, we will restore our body and mind to their original states. We will come to understand that although we are living in this external world, this is not our permanent place; we are merely visitors. Our permanent abode is inside. In fact, this Eternal Truth is the source of all life and the entire Universe. It is the ultimate goal, a final destination we arrive at through Realization and a place where we may remain forever.

For thousands of years, the great sages have sought to fully understand how Realization occurs. Yogis have identified many aspects of the mind and body that work to support the yogic experience. A comprehensive yogic science has emerged that recognizes the uniqueness of the human mind and body. If properly working, the mind and body enable humans to directly experience the Eternal Truth. This experience, as well as the bliss that ensues, is amazing. This unique capacity available to human beings helps us confirm that the very goal of human life is to experience yoga.

THE FOURTH STATE

The Indian science of traditional medicine called Āyurveda uses the word svastha to describe a healthy person. In Saṃskṛta, sva means “the Soul.” One who operates in this external world at the behest of the Soul is svastha. A svastha realizes the Truth and lives according to that Realization. In all the ancient Indian sciences, the idea of health directly or indirectly implies the existence of the yogic experience. It is the experience of countless yogis that demonstrates just how natural, and extraordinary, the yogic condition is.

Of the conditions that we experience in our daily lives, we are most aware of the waking state. We engage in various activities, including working, eating, moving from place to place, and conversing with others. Then, at the end of the day, we go home and at some point, go to sleep. At first, while falling asleep, we will experience a few minutes of dreaming. We see images in our minds, some of which make sense, and some of which may make no sense at all. Then the mind, in need of complete relaxation, transitions to deep sleep. While in this state, we have neither dreams nor consciousness of the external world. We may stay in this state for a period of time. After sleeping deeply for some time, we start to dream again. After dreaming, again we will fall back into a deep sleep. This pattern is repeated throughout the night until we arise in the morning.

These three natural states of being—waking, dreaming, and deep sleep—occur in other animals, as well as human beings. These are natural states and usually require little or no training. However, for human beings alone, there is a most important natural fourth state; it is the state of Samādhi, yoga, or sahajāvasthā. The word sahaja means “endowed by birth”; avasthā means “state.” Just as the ṛṣi reminded the prince of his natural abilities, this fourth state of mind is natural, but it is present only when there is total balance and health in body and mind. Once a yoga practitioner has significantly balanced his or her body and mind, and becomes firmly established in the experience of Samādhi, he or she will begin to notice the daily cycle of these states.

SAMĀDHI

Today’s definition of health is not comprehensive; unfortunately, many important qualities and ideas are left out. This is because most people acknowledge only three states of existence for the mind and fail to recognize this all-important fourth state.

If we are living balanced lives, we will automatically wake up at a certain time in the morning without the need of an alarm clock. At midday we will feel energized and motivated to work hard. Our appetite will arise at particular times throughout the day. We will feel sleepy at night and fall asleep without a struggle.

For the most part, our society recognizes our profound need for sleep, as well as the negative impact on our health if we lose the capacity to sleep. If there were a society that had developed the capacity to exist without sleep, its definition of health would not include good sleep.

Using this analogy, we might ask, Why do people lose the capacity to sleep? Some people might consume unsuitable food or worry too much. Some might crave material objects and work too hard in their effort to acquire them. Perhaps they have mental strain from a frantic lifestyle. They might simply stay up too late and not follow their natural sleep pattern. Most often, it is an unhealthy lifestyle that disrupts people’s sleep.

This is the same with the experience of the fourth state, or Samādhi. If our lives are in total health and balance, Samādhi will naturally occur regularly at a particular hour of the day. At such a time, the mind will start feeling a particular type of happiness and a separation from the external world. This feeling compels the yogi to find a private, quiet place to sit and meditate. Just as sleepiness is a sign to indicate that we need sleep, the practitioner’s craving for bliss is the sign that the conditions for Samādhi are available. If the practitioner heeds this message and sits in a calm and quiet place, he may reach this wonderful experience of Samādhi.

However, most of us are not around people who go into Samādhi regularly. Thus, we do not consider it as natural as sleeping or eating. Many believe that Samādhi is something novel to achieve through great and meticulous effort. That is in one way a mistaken idea.

The absence of the yogic condition is due to a wide variety of errors in our way of living today. Because these errors have been perpetuated over many generations, we have developed ignorance about the naturalness and even necessity of yogic experiences. Most have forgotten about the very existence of the yogic state and accept that its absence is natural. We understand little about what constitutes an ideal way of life and its benefits. Nor do we grasp the mechanics of the yogic condition, or understand the relationship between lifestyle and Samādhi. This loss of understanding about our true nature is a form of blindness.

KALI YUGA

We are living in the Kali Yuga, a vast cycle of time within the evolution of the universe. It is characterized by its drastic changes and turmoil. According to the ancient ṛṣis, this is an age in which human beings develop to be highly extroverted and thus lose their capacity for inward awareness of the Self. Though conditions are challenging for Enlightenment, one should remain optimistic and strive to develop a yogic lifestyle. Though an aspirant may not have the benefit of a Realized teacher, one should continue to seek and experiment on one’s own. This too may be considered a path toward Enlightenment. There are indicators and reminders everywhere—but only for a serious and true aspirant. For example, there is a story of a yogi who, as a child, saw lightning, contemplated deeply on it, and became Realized. Lacking any prior training, this young yogi used no formal device or yogic practice to reach the goal. This is one of many examples that remind us how the human system naturally possesses the capacity to experience yoga. But in order to access that capacity, we must have clear intentions.

OUR ULTIMATE GOAL

The culmination of yoga is Realization, which arrives through the experience of Samādhi. Each healthy human being should experience Samādhi. This central idea provides the context for us to explore the vast subject of yoga. With this purpose, we begin to understand why the sages recommend various disciplines and explain the impact those practices have on reaching this goal. Through the study of yoga, we can comprehend how the body and mind enable the yogic experience to manifest. If we are able to follow these yogic disciplines, we will maintain the health of this body and mind. In this way, our human effort will have maximum impact in this life—not simply for ourselves, but also for the benefit of others. We need not accept these ideas on faith alone; rather, we should test and validate them for ourselves.

Like the young prince who sought the benevolent ṛṣi’s advice to understand his true nature and where he had come from, we, too, must make a sincere effort to understand our full capacity as human beings. Then we, too, will discover who we truly are and recollect the Eternal Truth.